A Brief History of Dyslexia

Reproduced by kind permission of The Psychologist:

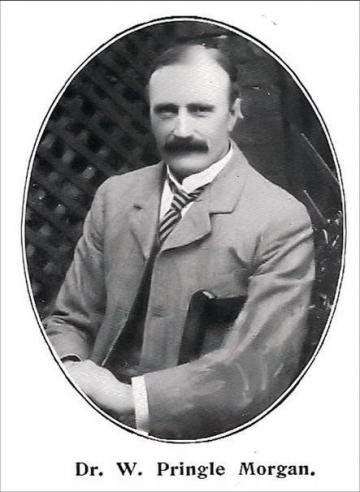

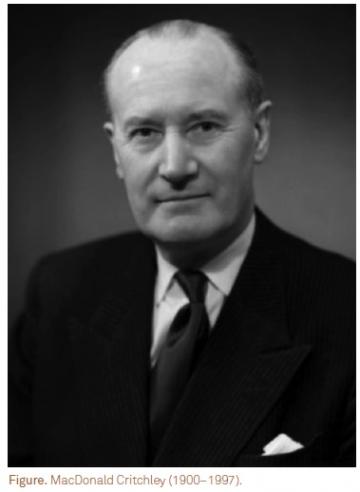

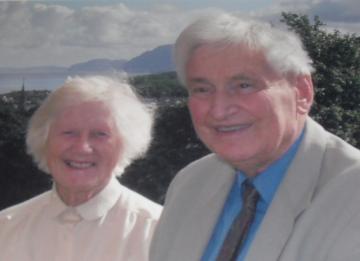

From top: Rudolph Berlin, Adolph Kussmaul, William Pringle Morgan, Macdonald Critchley, Sandhya Naidoo, Helen Arkell, Beve Hornsby, Margaret Newton, Marion Welchman, Elaine and Tim Miles, Mary Warnock, Jim Rose

It is 130 years since the term ‘dyslexia’ was coined by Rudolf Berlin, a German ophthalmologist and professor in Stuttgart. In the course of his practice, Berlin observed the difficulties faced by some of his adult patients in reading the printed word. He could find no problem with their vision. He speculated, therefore, that their difficulties must be caused by some physical change in the brain, even if the nature of this eluded him. The term Berlin used to describe the condition (meaning ‘difficulty with words’) would ultimately become more famous than he. One of the few biographic entries on Berlin describes him, somewhat poignantly, as ‘[the man] who named the ship, even though he never became her captain’.

Berlin himself had been influenced by the writings of another German, Adolph Kussmaul, a Professor of Medicine at Strassburg, remembered today principally for his work on diabetic ketoacidosis. It was Kussmaul who first identified the kind of difficulties Berlin described, in 1877, entitling them Wortblindheit (word-blindness). (Berlin coined ‘dyslexia’ to bring the diagnosis in line with contemporary international medical literature, which elsewhere described the similar conditions of alexia and paralexia.) ‘To Kussmaul’, writes James Hinshelwood, his contemporary, ‘must be given the credit of first recognising the possibility of this inability being met with as an isolated symptom.’

In the UK several Britons were working on the topic, including Hinshelwood, another ophthalmologist; James Kerr, a council medical officer; and William Pringle Morgan, a general practitioner. These three focused not only on word-blindness as an isolated symptom, like Kussmaul, but broadened accounts of the condition to include children. This weakened the explanatory power of brain injury or disease as dyslexia’s cause, which had hitherto been favoured, setting up a distinction between acquired and congenital word-blindness – the former occurring suddenly during adulthood, the latter present at birth.

Pringle Morgan’s and Hinshelwood’s reports of children with word-blindness are key to understanding dyslexia’s later history. Pringle Morgan’s is the more famous, perhaps partly because he humanised his account by using his patient’s name:

Percy F. – a well-grown lad, aged 14 – is the eldest son of intelligent parents, the second child of a family of seven. He has always been a bright and intelligent boy, quick at games, and in no way inferior to others of his age. His great difficulty has been – and is now – his inability to learn to read. This inability is so remarkable, and so pronounced, that I have no doubt it is due to some congenital defect.

Pringle Morgan’s description of Percy is almost identical to that of a child who Hinshelwood, in his first paper on congenital word-blindness, calls ‘Case 2’:

A boy, aged 10 years, was brought to me by his father on Jan. 8th, 1900, to see the reason of his great difficulty in learning to read. The boy had been at school for three years, and had got on well with every subject except reading. He was apparently a bright and in every respect an intelligent boy… It was soon evident, however, on careful examination that the difficulty in learning to read was due not to any lowering of the visual acuity, but to some congenital deficiency of the visual memory for words.

According to Peggy Anderson and Regine Meier-Hedde (2001), in one of the few academic accounts of this period in medical history, ‘This body of work became enormously significant for several reasons. First, the United Kingdom physicians wrote with a clarity and organization that heretofore had not been observed in the literature. Second, they turned attention to the plight of children, and, third, these physicians wrote numerous case reports on word blindness, which resulted in an accumulation of information about this enigma.’ To this list might be added Pringle Morgan and Hinshelwood’s role in associating dyslexia with high intelligence – a link that would endure for decades, with several ramifications.

Dyslexia, psychology and the rise of modern advocacy

Between the wars, research on dyslexia drifted in the UK, but expanded in the US – coalescing around one figure, in particular. Samuel T. Orton, a neuropathologist from the State University of Iowa, presented his first paper on word-blindness to the 1925 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association in Washington, DC. ‘In this work,’ write Anderson and Meier-Hedde, ‘which was destined to become a classic treatise in the field, Orton referred to the original work of Kussmaul, Morgan, and Hinshelwood, but drew different conclusions based on his own case studies and clinical observations. He disputed the premise that the roots of reading disability could be located in the angular gyrus and advanced his own theory that attributed reading disorders to a lack of cerebral dominance.’

Although Orton’s theory of cerebral dominance proved incorrect, it was key to shifting discussion of dyslexia’s aetiology toward theories of cognitive development. For Tim Miles, one of the pre-eminent researchers in dyslexia’s history (to whom we return below), ‘Of all the early pioneers he [Orton] was the one who, more than anyone else, put what we now call developmental dyslexia on the map.’ Orton was also one of the first researchers to advocate phonics instruction for those with dyslexia, the general approach still recommended today. In 1949 the Orton Society was formalised by Samuel’s widow, June, and continues today as the International Dyslexia Association.

By the 1960s dyslexia was attracting the attention of UK researchers again. Given the shift toward theories of cognitive development, psychologists were now foremost. In 1962 the Word Blind Centre opened in Bloomsbury, founded by the Invalid Children’s Aid Association under the direction of Dr Alfred White Franklin. Formed after a conference on the subject at Barts Hospital, the Centre’s first committee consisted of Macdonald Critchley, Oliver Zangwill, Patrick Meredith, Maisie Holt and Tim Miles – neurologists or psychologists all, and amongst the foremost names in the field at the time. The Centre’s first director was Alex Bannatyne, succeeded by Sandhya Naidoo, an educational psychologist.

In the years that followed, a series of seminal texts on dyslexia emerged, authored by some of those attached to the Centre. In 1970, Critchley published his sympathetic account, The Dyslexic Child, which identified ‘developmental dyslexia’ as an issue requiring urgent official attention. In 1972 Naidoo published Specific Dyslexia, the first account in Britain to make a systematic comparison of dyslexic and non-dyslexic children, which remains instructive today. Focusing on how children develop literacy, Naidoo argued that, ‘Preventive and supportive steps taken early are immeasurably more humane and fruitful than attempts to remedy a problem which becomes increasingly complex as the child grows older.’

To expedite such steps, and following the closure of the Word Blind Centre in the early 1970s, several organisations dedicated to dyslexia were founded. They included the Helen Arkell Dyslexia Centre (1971), the Dyslexia Clinic at Barts Hospital (1971), the British Dyslexia Association (1972), the Dyslexia Institute (1972), the Language Development Unit at Aston University (1973) and the Bangor Dyslexia Unit (1977), amongst others. Some of these remain in operation today, providing a source of support for children, their parents, and adults with dyslexia, as well as professionals working in the area.

These organisations worked alongside other researchers, campaigners and practitioners in psychology and education. Notable figures of the period include, but are not limited to: Bevé Hornsby, head of the Dyslexia Clinic at Barts; Marion Welchman, who orchestrated the creation of the British Dyslexia Association and was involved in the early days of the Word Blind Centre; and the actress Susan Hampshire, former president of the Dyslexia Institute, who has dyslexia herself and was awarded the OBE in 1995 for her advocacy work. Women were not the only voices in the struggle for the rights and recognition of people with dyslexia, but theirs have been crucial.

The struggle for recognition

The years following the opening of the Word Blind Centre in 1962 are key to dyslexia’s later history. They marked not only the start of modern research on, and advocacy for, the condition – which would ultimately result in recognition by government and protection for people with dyslexia under legislation like the 2010 Equality Act – but also the rise of the notion of dyslexia as a ‘middle-class myth’. Through this, dyslexia was construed as a pseudo-medical diagnosis used by middle-class parents to explain their children’s poor performance in reading – an argument that has dogged campaigners ever since. Early reticence to acknowledge the condition came from educational, medical and political quarters.

One of the historical factors driving the notion of ‘middle-class myth’ was reliance on what became known as the discrepancy diagnostic model. Under this, a person could only be considered dyslexic if they exhibited a marked difference between their reading age and general intelligence (IQ), in favour of the latter – an argument with precursors in Pringle Morgan’s and Hinshelwood’s accounts of their ‘otherwise bright and intelligent’ child subjects. It was this model that was initially relied upon by many of the organisations above. Naturally, such a definition was desirable to parents wanting to prove that, despite their child’s struggle in one academic area, their general intelligence was unaffected.

Coupled with this, dyslexia (then as now) was being diagnosed in higher proportions in children from wealthier socio-economic groups. Differential access to dyslexia specialists and their tests was a reason for this, sparking accusations that dyslexia was curiously prevalent in Surrey. (Today, Dyslexia Action, the British Dyslexia Association and the Helen Arkell Dyslexia Centre are all located within about 20 miles of each other – across the Surrey/Berkshire border.) Parents with higher education levels were also more likely to be aware of the condition, and earlier. Again, it is notable that the children considered by Pringle Morgan and Hinshelwood, from what we can derive of their backgrounds (through references to their education, father’s occupation, and so forth), were firmly middle-class – presumably for similar reasons.

But if historical aspects like this explain dyslexia’s association (and disassociation) with certain socio-economic groups, they do not fully explain accusations that the condition is a myth. Why has there been a reticence to affirm dyslexia’s existence?

For some, most obviously policy makers, the reason for rejecting the dyslexia label has been pragmatic. In the 1970s passing reference was made to the condition in the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act, further investigated by the Tizard Report two years later, Children with Specific Reading Difficulties. The latter claimed to be ‘highly sceptical of the view that a syndrome of developmental dyslexia with a specific underlying cause and specific symptoms has been identified’. This despite the evidence, described above, that was emerging during this period.

In 1978 the Warnock Report on special educational needs was published by the then Department for Education and Science. Here, the government’s antipathy to the term was proactive. The report’s author, Baroness Mary Warnock, recalls being summoned by a senior civil servant of the Department, who told her that she ‘should not suggest that there is a special category of learning difficulty called dyslexia’. Presumably, this reflected an unwillingness by the Department to expend resources on the condition, with estimates suggesting that up to 10 per cent of the population might be affected.

In the aftermath of the Warnock Report, the government fudged, justifying its reticence to engage with questions about dyslexia by claiming that it did not recognise distinctions under the umbrella term ‘specific learning difficulties’. This eventually changed in 1987, when the government announced (a little ironically) its desire ‘to dispel a myth’: ‘that the Department of Education and Science and its Ministers do not recognise dyslexia as a problem’. In fact, ‘the Government recognise dyslexia and recognise the importance to the education progress of dyslexic children, their long-term welfare and successful-function in adult life, that they should have their needs identified at an early stage. Once the assessment has been made…the appropriate treatment should be forthcoming.’

In 2009 the final report of the Rose Review, appointed by the government as an independent group ‘to make recommendations on the identification and teaching of children with dyslexia’, defined dyslexia unequivocally:

Dyslexia is a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed. Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities. Co-occurring difficulties may be seen in aspects of language, motor co-ordination, mental calculation, concentration and personal organisation, but these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia.

Psychological diagnosis and social construct

In some quarters, however, the dyslexia debate continues – principally educational psychology. The most notable recent criticism of the term is the 2014 book The Dyslexia Debate. This does not query ‘whether biologically based reading difficulties exist (the answer is an unequivocal “yes”), but rather how we should best understand and address literacy problems across clinical, educational, occupational, and social policy contexts.’ One of the factors preventing such understanding, it is claimed, is the word itself: ‘In respect of word-reading difficulty, the construct reading disability is surely preferable for use by both researchers and clinicians. This term dispenses with much of the conceptual and political baggage associated with dyslexia.’

What’s interesting, from a historical perspective, is that such definitional debates have been seen before. In The Dyslexia Debate, it is lamented that, ‘Clearly there are very significant differences in the ways in which this label [dyslexia] is operationalized, even by leading scholars in the field’ – a polysemy, it suggests, that undermines the term. In 1896, Hinshelwood made the same point: ‘the word [‘word-blindness’],’ he noted, ‘has frequently been used by writers loosely with different meanings attached to it and therefore it has been frequently misleading.’ Hinshelwood’s solution, rather than jettisoning the term, was to better define it – ‘The fault lies not in the word,’ he suggested, ‘but in the fact that those who use it have not always a clear conception of what Kussmaul meant by it.’

In querying the term ‘dyslexia’, what recent criticism does highlight is that dyslexia is more than a psychological classification, the parameters of which are being continually debated as per the scientific method. Dyslexia is also a ‘construct’ that meets, in the words of The Dyslexia Debate, ‘the social, psychological, political and emotional needs of multiple stakeholders’. This shifts the emphasis toward how dyslexia has been constructed through disciplines like ophthalmology and psychology, and the advocacy of the actors described above – and how changes in society, not just in medical science, enabled dyslexia to emerge.

Before the advent of highly literate societies, dyslexia could not exist in the way that we understand the condition today – notions of ‘disability’, learning or otherwise, are dependent on time and place. Dyslexia’s emergence coincided with other changes in Western society around the time Kussmaul, Hinshelwood and their peers were writing. These included the advent of widespread literacy and schooling, the expanding medical profession, and the increasing requirement for people to process linguistic information in everyday life. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, dyslexia advocacy was entwined with changing gender roles, the expansion of civil society, and the early rise of what would now be called the ‘professional parent’.

To gain political purchase for such a cause, the complexities of dyslexia research, at least in the public sphere, were necessarily simplified, so that the cause could be understood and thus advocated for in a variety of settings. Such reduction, alongside the absence of a precise and universal definition, exposed the dyslexia label to accusations of politicisation and conceptual simplicity. Adding to the complexity, definitions and understandings of any medical condition, whether a learning difficulty or otherwise, necessarily develop over time.

In this way, it is useful to think of dyslexia as both an ongoing psychological diagnosis and a social construct, with all that entails. While drawing attention to the cultural meanings around a condition like dyslexia is important, especially when looking at its history, it is also necessary to remember that such meanings refer, ultimately, to a group of people who struggle with a skill fundamental to life in contemporary society. Irrespective of current debates around the utility of the term, the work of the researchers, practitioners and campaigners discussed in this brief history has been crucial in helping young people and others overcome this struggle.

Sources

- Anderson, P.L. & Meier-Hedde, R. (2001). Early case reports of dyslexia in the United States and Europe. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34(1), 9–21.

- Berlin, R. (1887). Eine besondere art der Wortblindheit (dyslexie). Wiesbaden: J.F. Bergmann.

- Critchley, M. (1970). The dyslexic child. London: William Heinemann.

- Elliott, J.G. & Grigorenko, E.L. (2014). The dyslexia debate. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hansard. (1987, 13 July). Dyslexia. HC Debates, vol. 119, cc949–956.

- Hinshelwood, J. (1896, 21 November). A case of dyslexia: A peculiar form of word blindness. The Lancet, 1451–1454.

- Hinshelwood, J. (1900, 26 May). Congenital word-blindness. The Lancet, 1506–1508.

- Hinshelwood, J. (1917). Congenital word-blindness. London: H.K. Lewis.

- Kussmaul, A. (1877). Diseases of the nervous system and disturbances of speech. In H. von Ziemssen (Ed.) Cylopedia of the practice of medicine (pp.770–778). New York: William Wood.

- Miles, T.R. & Miles, E. (1999). Dyslexia: A hundred years on (2nd edn). Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Naidoo, S. (1972). Specific dyslexia. London: Pitman.

- Pringle Morgan, W. (1896, 7 November). A case of congenital word blindness. The Lancet, 1378.

- Rose, J. (2009). Identifying and teaching children and young people with dyslexia and literacy difficulties. London: Department for Children, Schools and Families

- Wagner, R. (1973). Rudolf Berlin: Originator of the term dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia, 23(1), 57–63.

- Warnock, M. (2013, 8 August). Interview w/ Maggie Snowling. St John’s College, Oxford.